Prelude to a Royal Death

Abrasive cries and wales screamed forth into the Andean skies as the sacred Apus, near and far, braced themselves, horridly anticipating more...

Not one observer could stand to watch. Even the birds, propped high on the church's façade had to turn away from the gruesome view surreally befalling so many stories below on the grounds in front of the Santo Domingo Church.

The brightest light had just been extinguished right as the last sawing sounds abruptly ceased.

I awoke in a sweat, wondering where I'd been. The clock read: 10:42 p.m., as I shook my head, fearing the vivid visions might have lasting effects.

It'd been three weeks since my arrival to the ancient capital. Since then, I'd been staying at Hostal Iquique on Calle Recoleta, right at the border between old and new town Cuzco. I opted for this location, mostly, given my familiarity with the neighborhood, following my previous two lengthy trips to the Andean city. If anywhere in Cuzco formed my haunts, Calle Recoleta, a 10-minute walk from the Plaza de Armas, would be my claim.

Hours before, I had solidified plans for a four-day venture along a route that defined an empire. More specifically, a route that, over time, resolved a conflict of two empires, between the reigning champions of both Old World and New.

In my many years of study and travel, I had read and heard about the tales of the legendary Sapa Incas following the 1531 Spanish incursion: Manco Inca and his many iterations in both Cuzco and beyond; as well as his three Vilcabamba-based sons, Sayri Tupac, Titu Cusi, and Tupac Amaru.

I'd also been told by my friend in Lima that the long road to Vilcabamba was one of the most fascinating trails and tales to be had whilst in the Cuzco Region; at least concerning the later decades of Incan existence and resistance, years following the initial Spanish conquest of Perú.

The interchange with José was integral in my decision to venture to the Last Refuge of the Incas.

"Si realmente quieres un viaje, no veo ningún lugar mejor para ir. (If you really want a trip, I don't see anyplace better to go.)" he affirmed.

Having my sights set on returning to Cuzco and the Sacred Valley but not much more, I responded, "Pero no entiendo por qué. (But I don't understand why.)"

José demanded, "Patricio! Recuerda las historias que te conté toda la semana pasada. Lo verás más claro! (Patricio! Remember back to the stories I told you all of last week. It'll become clearer!)"

My friend's message was clear. We'd visited the best museums in Lima, walked all over the capital city talking about Peru's history, ancient, modern, and present. We had eaten meals together, both in public and at his home, discussed even more history, myths, literature, and music. And now was the time to delve deeper into making all of this come fully alive. I knew he was right. For I simply needed to conjure the courage to venture beyond my cultural comfort zone.

But, first, I needed real rest. I hadn't been sleeping well for nights. So, after my first flash of nightmare, surely the result of a tale José once told, I had little choice but to succumb to my slumberous fate.

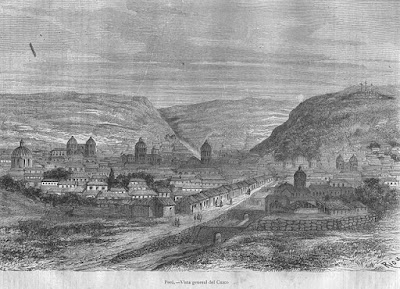

The brilliant, blue-skied morning in the former Incan capital was as marvelous as ever. Birds soared majestically from places infinitely high, while others used their legs to scurry about on the earth, at times playing; at others, hustling for crumbs there from human error. Still others took respite, propped on the shapeshifting building facades of the growing colonial Andean jewel. It was late September in Cuzco, 1572.

With all of this constant construction, it seemed that the newest rulers in town still weren't content. Four decades on, they continued to refuse to preserve any of the old rulers' buildings. Instead, like any veritable dominator, the Iberians opted to assert their control by destroying Incan structures and inserting hastened Old World architecture on top of the formidable foundations masterly built by their predecessors. Palaces, royal quarters, common buildings, and more, for the examples around the city were myriad and endless.

None, however, was more noticeable than the location at the hub of all the action: the Dominicans' noteworthy, towering church constructed abruptly atop the ancient foundations of Cori'cancha, the Incas' Temple of the Sun. This was the beyond-sacred Incan site which for centuries was the physical manifestation of the symbolic Belly of the Universe, or El Ombligo del Universo, the tethering point about which the rest of the Andean-long empire's sacred sites orbited, calibrated, and synergized.

Cori'cancha was, at its source, the place from which the Incas themselves, individually and collectively, tethered their souls. It was the symbolic location from which balance and guidance were drawn, and the depository to which their deepest woes and illusions were surrendered, during moments expansive or narrow, over durations wide or short.

At its core, Cori'cancha gave deepest meaning to the word "capital," for the entire history of Incan existence is rooted in and spans from the earth beneath this temple. It was the cosmological, spiritual, practical, and political hub of the Incan universe; the equivalent to Mecca or Medina for Muslims, Jerusalem for Jews or Christians, or the Vatican for Roman Catholics.

Circa 1572, howbeit, the only evidence of centuries' past unmistakably jutted out from the church's base. This most intricately formed stonework was probably the greatest surviving relic of architecture in the former Empire. Although keeping these lasting foundations could've been taken as a Spanish ode to the Incas and their high-level abilities, more probable was its placement as a purposive reminder to the natives (or any onlooker) of exactly who was in charge. Only being left with the solid-rock base, spanning church-width and -depth, must've felt utterly degrading to any Inca passerby of that age or any age.

As if losing their grand Temple wasn't enough for the native Andeans, a new edition only intensified Incan reactions to the site: Santo Domingo's imposing bell tower. It was a relative novelty which hung especially high over its courtyard and, noticeably, everything else. Needless to say, this was the overarching intention of Iberian architects and a physical result whose visual and auditory presence brought jubilance to anyone Spanish from the bordering Avenida del Sol back far over an ocean to the Motherland peninsula. To native Andeans, however, the bell tower just loomed, uncomfortably nudging at native memories and invariably altering their focus in the present moment.

Neverminding the traumas of present and past, the morning of September 24, 1572 was like any other in the high-propped Andean basin city. All except for one thing: the short-awaited date had arrived. It was the designated day of greatest grief, for their Sapa Inca was due to be dismissed from Earth. The ruling from harsh Spanish judges, in spite of fervent calls for fairness and impartiality, had been rushed, skewed, and definite: death to the Sapa Inca, Earth's embodiment of the Sun, by decapitation on the grounds in front of the Santo Domingo church. And, thus, at the foundational base of Cori'cancha, the Temple of the Sun, his symbolic and, formerly, literal home on Earth.

Thence, thousands of Cuzqueños hastily traveled from distances short and substantial. They needed no calendar to guide them, for they knew intuitively, in their tortured hearts, that today the tears would be unleashed. Many more than yesterday and, possibly, surpassing those of tomorrow. It was strange: they were eager to be present yet, understandably, forlorn and reticent to arrive.

Meanwhile, the stage was set. A scaffold with a black drape hanging over its platform had been erected in front of the church. As thousands of Incan bodies began to congregate, very quickly, little space was left to comfortably observe the scene. There were certainly more eyewitnesses present than could be assessed with the eye; these were those old souls now watching from the ethereal realm, holding hurt over the whole event and pity on everyone agonizing the royal loss before the loss.

The Sapa Inca was then led out from captivity by what appeared to be a hundred guards. That's when the cries to the heavens began. 10,000 native souls chaotically considered 10,000 or more ways to make this day simply not be, to rewind or forward time to a moment and place less tragic. The audible collective pain was so profound, its shrill soon became too much to take. It grew in such severity that it easily exceeded any decibel level of lament hitherto experienced in Incan history.

On that cool Cuzco morning, even the sacred Apus, those wise, knowing Andean peaks, anguished in the imminent loss of their ultimate son.

I awoke, this time, in a violent, second-long shake. The ear-piercing cries were, again, too much for me to endure. God! What was that?! I thought, as I tried to recollect the order of visions, while hoping to exclude the mood.

I needed my journal and pen. So I quickly rose to flip on the lights, eager to note every detail of my glimpse into Andean history. As I jotted down the important highlights, I began to piece together the storyline of my dream with tidbits based on what José had told me in Lima and any of my previous knowledge from readings about 16th century Perú.

Here's what I could tell so far:

|

| The assassination of Tupac Amaru |

Inca Tupac Amaru was the last official Sapa Inca, who, in addition to his predecessors Manco Inca, Sayri Tupac, and Titu Cusi, was responsible for leading the loyalist Incas in their last decades of holdout from frequent Spanish offenses: military, clerical, and otherwise.

Following the conquistadors' taking of the city of Cajamarca in 1531, and subsequent conquest of Cuzco in 1532, the capital had been under Spanish control. Although Iberian rule was unstable, the loyalist Incas, nevertheless, needed to negotiate their new role as challengers to a new boss in town.

At first, most native Andeans were conciliatory, with many even joining the old-worlders. Then, circa 1535 and 1536, a number of formidable plans and rebellious actions yielded fierce, key engagements carried out so as to attempt to restart Incan momentum. This was the loyalist Incan movement.

I knew of some of these important back-and-forth conflicts between the Spaniards and loyalist Incas, but, even so, I couldn't recall many of them in that hazy, post-vision moment.

I did, however, remember José specifically mentioning the importance of the high-mountain niche of Vitcos and the lower-jungle retreats of Vilcabamba, days to the northwest of, and far from contact with, then-colonial Cuzco. This was the region where the loyalist Incas eventually took necessary refuge for approximately 33 years, and where a remarkable portion of the Spanish conquest of Perú's later history is held.

This time-span and place thoroughly interested me. And I, in spite of the limitless lessons with José and others, still needed to learn more. My impatience was running high at this late hour. So, before any kind of travel would be happening, I had to scurry my mind for more.

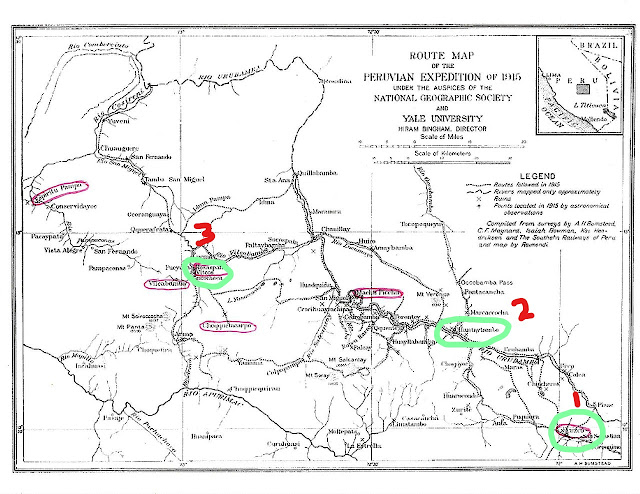

An insight from Bingham's writings shot back to mind:

After months of astonishing adventures retracing Simón Bolívar's road through Colombia and Venezuela in 1906-1907, Bingham had been ready to return to his intellectual fascination in South America. The 1908 proposal from the First Pan American Scientific Congress would allow the Yale professor to travel to Chile, after which he would embark on his second expedition through the continent: a retracing of the trade route from Buenos Aires to Lima.

This experience would open up to him the realm of the Southern Andes, and, in particular, the region of Bolivia and Peru. Nothing would ever be the same for the fledgling professor. Of this, Bingham wrote to his wife toward the tail-end of his 1908-1909 journey:

After venturing over the limitless pampas of Argentina, having now entered and felt the Andes like I'd never thought possible, there is now a question left burning brightly in my heart: where in these unending layers of topographic Andean wrinkles lays the true last capital of the Incas?

I'm certain that the "cradle of gold," or Choquequirao, is not this place, as Raimondi and others have theorized. In spite of the immensity and glory that is this ruin site, I know that there is much to be discovered to the area north of this location, in an area referred to as 'Uilcapampa'. The story of the last four Incas is held within this region. For this reason and more, I must return.

I also remembered something from the later years of loyalist refuge. The story of the pursuit of young Tupac Amaru, following the Spanish storming of the retreats at Vilcabamba. It was only after a many-week chase of him in the further reaches of the deeper jungle, there, that he and others were finally captured and taken prisoner by a small group of Spaniards. I was particularly fascinated by this story.

I knew that this spellbinding story began in the capital of Cuzco, entered into and along the magisterial Sacred Valley, and led up to and included the high-altitude glory of Vitcos and low-altitude lushness of Vilcabamba; these were the places where this plot unfolded during the last days and years of the Inca Empire.

And, coincidentally, as my tired eyes started to squint, this historic route would be the setting for my four-days' journey to, what Prescott called, "the remote fastnesses of the Andes." An adventure from high mountains to veritable jungle, and from purely present to ancient yet active past.

|

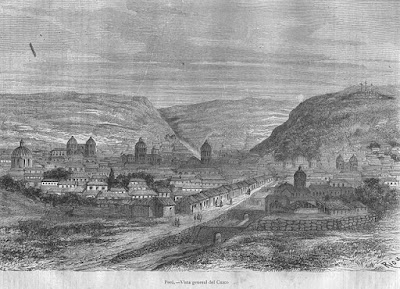

| Peru and Cuzco city map, Antwerp, 1578 |

From the safe confines of Hostal Iquique, my short stint of inspired, wakeful study was interrupted by an impending return to sleep. Perhaps more clarity was on its way in the coming moments and days. Intriguingly, as would be the case from here forward, another vivid storyline was revealed during this two-hour delve into lucid dreaming, post-madrugada.

"Retirada! Retirada! (Retreat! Retreat!) screamed the coarse commander from the saddle of his valiant horse. "Su número es demasiado grande para que podamos luchar. (Their numbers are way too large for us to battle.)"

Despite the tens of conquistador horsemen, triple parts footmen, and hundreds of native auxiliaries being primed for battle, the Iberian's vigorous contingent discouragingly backed down. They, as hungry as ever, had wanted nothing more than to abolish the Sapa Inca at the base of the magisterial valley below.

This was the same leader, Manco Inca, who'd been the Spaniard's necessary, though at times, unruly Incan puppet leader over the past three years in Cuzco. The same leader, moreover, who had just promised gold treats, but who had instead been planning a rebellion.

Based on the mesmerizing, many tens of thousands of Andean soldiers dotting the deep depths of the river valley thousands of feet below, the event was clearly premeditated. The Spaniards, thus, had no other recourse; they had to retreat from their bird's eye perch overlooking the sacred Valley of Yucay and promptly return to the secure basin of their colonial capital.

Once back in Cuzco, Brothers Pizarro and other high Spanish officials engaged in a heated discussion. "Ese maldito traidor! (That damn traitor!)" Francisco exploded. Wasting no time, he turned angrily to his commander and brother, Hernando, "te dije, Comandante, que no creyeras su promesa! Nos la ha jugado a lo grande, ahora... (I told you, Commander, not to believe his promise! He's played us big time, now...)"

Hernando could only sink his head, as he stared into a void in the spacious palace. His older brother's rampage, however, was unrelenting. "Probablemente ha estado planeando esta rebelión durante años! (He's probably been planning this rebellion for years!) Francisco's ire inflamed. "Estamos jodidos. Completamente jodidos! (We're screwed. Utterly screwed!)"

Everyone present shuddered at the Governor's explosion. But they also knew that there was one main culprit in the matter. Hernando Pizarro was, after all, the one who allowed Manco Inca to leave Cuzco following the latter's promise of gold riches. This Pizarro was, like many conquistadors would be, up for the trade-off between risk and reward. However, this move was taking quite a chance, since it was known that the Sapa Inca still had formidable support all over the region. One key breakthrough, and a rebellion could occur.

Just what the Sapa Inca had in store was really only known to the Spaniards following their failed attempt to nip the rebellious Incan bud. Ultimately, this native bud was too big. Hence, the worrisome reaction and resulting lividity of leaders.

"Y ahora qué, Hernando? Qué demonios vamos a hacer ahora?! (Now what, Hernando?! What the hell are we to do now?!)"

Sweat poured from the brows of the conquistadors, as they lamented their strenuous sitch. Had the commander not been a relative, the Governor might've killed him. And everyone in the main plaza headquarters knew it, too.

The Iberians' precarious situation and anticipation of the inevitable, giant Incan incursion was perfectly summed up by Brother Juan Pizarro in two fitting, familiar words: "Estamos jodidos! (We're fucked!)"

My eyes shot open, as I gasped for air. "What the f#&^?!" I cursed, unnerved by the wild content of my dream. Though similar night-visions had visited me over the past couple of weeks, none had been more palpable and paranoid as this one. Is this what happens to others who overextend their stay? I pondered. Maybe I had been in Cuzco for too long, after all? Regardless, I knew that later in the afternoon I would have to travel, so I opted to get a head-start on my day.

Having spent the previous three weeks in the city and surrounding area, familiarizing myself with its present and past, these would be my last few hours in the former Inca capital. That is, until my return in four days' time. And, as I would find, my late-morning and afternoon of roaming around Cuzco would be time well-spent.

Call it a gift, or call it a debility, but having the ability to space out has always been a habit of mine. And, it's a practice I've enjoyed since I started my travels twenty years' ago. To me, it's the best way to have a direct experience with something new or even something familiar; a method of seeing the latter as if for the first time.

Hence, my walking in a trance through the fascinating narrow streets of the city-center was a perfect means of meditation. It was also an effective approach to enter the realm of history in a very ancient place.

"Patricio," José's voice shot through. "No olvides que los últimos cuatro incas no tuvieron acceso facil a Cuzco en un momento dado. Por supuesto, Manco Inca y sus dos primeros hijos vivieron allí durante años, hasta la rebelión que fue el Asedio del 36. (Don't forget that the last four Incas didn't have easy access to Cuzco at a certain point. Of course, Manco Inca and the first two sons lived there for years, up until the rebellion that was the Siege of '36.)"

"Pero (But)," José continued, as his passion fully shone. "Una vez que se estableció el estado en Vilcabamba, Manco Inca, Sayri Tupac, Titu Cusi y Tupac Amaru fueron en su mayoría o totalmente ajenos a un lugar que era parte integral de la existencia de los Incas. Y no hay que dudar de la angustia que esto causó a todos ellos. (Once the state in Vilcabamba was established, Manco Inca, Sayri Tupac, Titu Cusi, and Tupac Amaru were mostly or totally outsiders to a place that was integral to the existence of the Incas. And never doubt the distress this caused them all.)

"Aunque Titu nació en Cuzco y regresó un par de años después de los sucesos de 1539, se dice que el dúo hablaba de su sueño de tener algún día acceso a un lugar que sólo su padre y muchas generaciones de sus abuelos conocían íntimamente en su forma pura. (Even though Titu was born in Cuzco and returned for a couple years after the events of 1539, it's said that the duo would talk about their dream of one day having access to a place where only their father and many generations of their grandfathers intimately knew in its pure form.)"

Tropical birds trilled myriad lines of melodies, fusing to form a grand avian symphony of sound, which reverberated into the depths of the selva.

Walking through the verdant forests of vilca trees, the two boys wound their way on a trail back to the town center at Tendi Pampa. "Hurry Tupac, the ceremony's about to start!" Titu called to his little brother, who, circa 1555, had just turned 10.

It was the day of the summer solstice, or Inti Raymi, when the celebrations all over the Andes was never greater.

"Wait up, Titu! You're always going way too fast!" Little Tupac lamented.

When the crowds had all arrived at Vilcabamba's Temple of the Sun, the inseparable pair looked on in amazement as the hallowed sun disk, the Penchao, was revealed for the onlookers to see. A collective hush silenced the din of anticipation when the sun hit the etched mastery of the giant gold coin, the sacred symbol of the sun for the Incas.

Everybody knew it was the same Penchao that had been taken from its niche in the comforts of the temple of Cori'cancha, the true center of the universe for these Andean people, and transported with the Loyalists during their exodus from the capital.

"Our father used to talk about Cori'cancha. And, even though I never got to see it in its original form, he used to say how amazing it was to walk through its rooms." Titu said.

"Why? What was there?" little Tupac asked, mystified by the shine from the large disk.

"Everything was there, Tupac! The Penchao was there. All of the gold statues and figurines you see here and more were everywhere imaginable! There were even more mummies of our grandparents inside also."

"Wow!" Tupac marveled, as the 1555 festivities began, with Brother Sayri at the healm.

"The place was huge, too!" Titu whispered. "Not like the size of Tendi Pampa. Gosh...this place is so small compared to Cori'cancha. And that's not to mention the grandeur of all of Cuzco!"

Tupac's imagination flew. He wondered what this place called Cuzco must've looked like. His brothers, Sayri and Titu, had gotten to see it, but he'd been so far shut out from having access to it. Even with the place having changed so much for over two decades, with Spanish architecture taking the place of Incan constructions, the youngster would always yearn to be present in the sacred Andean basin.

"Don't worry, Tupac." Titu consoled his brother. "You'll be able to go there one day to see some of what's left from our history. Father used to always tell me: 'Son, Qosqo (Cuzco) is where all of us are from, and that's why we'll all return there one day'."

José's voice returned. "Tupac sólo podía soñar con este lugar que estaba tan cerca en su corazón y en su alma, pero que, desgraciadamente, sentía tan extraño a sus ojos y a su cuerpo. Aunque Titu había visto la capital dos veces, Tupac tendría que esperar mucho tiempo para una oportunidad. (Tupac could only dream of this place that was so close in his heart and soul, but, unfortunately, felt so foreign to his eyes and body. Even though Titu had seen the capital twice over, Tupac would have to wait a very long time for an opportunity.)"

As I strode along various streets all through the entirety of the ancient city-center, I could see what Tupac Amaru had been missing out on for the majority of his life. Even though he was brought back to this place, the heart of the Inca Empire, just prior to his last days, he wouldn't have had the opportunity to enjoy the sights that his two brothers and others had seen during their time in the capital.

Here, I figured it fitting: why not take in the sights as an ode to the last Sapa Inca, while enjoyed from a vantage point and perspective that he couldn't experience and, unfortunately, wasn't afforded.

While I walked the stone paths, the list of sites of historical intrigue seemed endless: Cori'cancha, "the Temple of the Sun" (Santo Domingo Church); Hatun Rumiyuq and the former palace of Inca Roca (the Archbishop's residence, where the 12-angled stone rests); Tuq'ukachi, "the opening of the salt" (San Blas neighborhood); the palace of Viracocha Inca (the Cathedral); Amarucancha, the palace of Wayna Qhapaq - Huayna Capac- (Church of the Society of Jesus, the Jesuit Church), among many others.

Tupac Amaru wouldn't have seen many of the original constructions of his ancestors; for only Inca foundations would've been used as bases for Spanish buildings erected atop. He, too, wouldn't have seen all of the mentioned Spanish constructions, since some were still in the process of being built, like the San Blas Church and the Cathedral. And others still hadn't even been initiated, circa 1572, like the Jesuit Church, a project that didn't start until four years' after Tupac's arrival and prompt assassination.

As I sat, watching the Plaza de Armas' action from my perch on a café balcony, I thought back to the fate of the late Sapa Inca's 18th-century namesake. José Gabriel Condorcanqui (1738-1781) had led a native rebellion in the Viceroyalty of Peru with the hopes of overthrowing what he saw as corrupt and abusive colonial rule. His fate, circa 1781, was to be quartered at the colonial center of town, the Plaza de Armas.

Inca Tupac Amaru's fate, circa 1572, had been death by severance in front of the Santo Domingo Church at the foundational base of Cori'cancha, the Temple of the Sun, the Incas' forever center-of-it-all.

I thought reluctantly back to the original dream from the previous night. The chilling cries and wales still uncomfortably subsisted in my mind. This, needless to say, added a sobering element to my afternoon, while I considered the last Sapa Inca's tragic final moments.

In spite of these darker days of history, my last hours in Cuzco had been mostly satisfying and complete, as I took in the cool Andean air and strong sunshine. I now necessarily anticipated my next move: on my new adventure, a mobile one, spanning the length and breadth of a good portion of the heart of the Cuzco Region.

Thus, an hour later, following the necessary preparations and my customary afternoon nap, the moment would finally be here. It would happen at 4 p.m., Peruvian time, crosstown at a new and unfamiliar departure point.

Fast-forward to then, approximately 4:10 p.m. And, there, in the modern comforts of a white Toyota minivan in the Santiago Barrio of Cuzco, where I was struck with the realization that in the coming hours and days my reality was to shift from the familiar to the foreign: in terms of geography, climate, history, and much more.

Withstanding, I sat, nervously anticipating the arrival of my carmates. An onslaught of anxiety flushed through my body. My perception trembled. My breath caved. My stare was blank, as residual images from the two rounds of dreams rushed through my mind, awing me to the prospects of this venture. To regain my wits, I desperately reassured myself that I was surely in the right place, and on the proper journey.

The words of José rushed back into my awareness: "Tienes que hacer que todo esto valga la pena! (You need to make this all worth it!) Then, proclaiming emphatically, "qué diversión tiene la vida sin aventuras, Patricio?! (what fun is life without adventure?!)"

I, once again, knew my Limeño friend was right.

Meanwhile, my wait for the others finally ended. Within minutes, the local Peruvian passengers began filing into the small vehicle. That is, all but one. Accordingly, five out of six of us silently waited, ready as ever.

Our departure point was fortunately in the Santiago Barrio, one of the last barrios just short of the Cuzco escape route up the hill and out of the basin to Chinchero, via that slow-climbing, slanted road. Lucky enough, I thought, at least we were assured of avoiding late afternoon Cuzqueño traffic.

From the advantage point of my throne in the backseat of the minivan, I relished in observing the to-and-fros of the local foot-traffic. Nothing like watching the movement of a people, a city, a country, and a culture that I deeply cherish.

I thought back to my three years as an undergrad at UC Davis. The freedom in its various facets, the new environment, the blank slate. There was also the remembrance of my intent on following my passion for history and culture. In particular, it was my love for Latin America that I was deliberate in following.

I sought taking any and all courses related to the history and anthropology of Mexico, Central America, and, most importantly for me, South America. I was lucky. Almost all of my professors specialized in Latin America, while a majority had a focus on South America, the Andes, and, notably, Peru. There were specialists in ancient history, colonial history, and modern history. Others had focuses in cultural customs, music, and dance. Another three instructors concentrated on a variety of emphases, be it Globalization, migration, society and social class, among others, either in Lima, Cuzco, or in the Amazon. My three years of classes at Davis I found to be simply fascinating, and were a perfect stepping-stone into the education that I'd always envisioned.

It was incredible. Here I was, traveling through landscapes that I'd really only reached through the reading of millions of words, the considering of thousands of ideas, the listening to hundreds of lectures, and the viewing of a handful of films.

As I savored this feeling, one of my favorite professors came to mind. Professor Charles F. Walker is considered the foremost authority on the history of colonial Cuzco, and its greater region. He's written a number of very important books about colonial Lima, colonial Cuzco, and the aforementioned José Gabriel Condorcanqui, or Tupac Amaru II, the rebel who led an eventually unsuccessful insurrection against local Spanish rule in the 1780s.

Professor Walker, or Chuck, is a vibrant, amiable, and hugely insightful person, generally, but, specifically on the histories of Latin America, Peru, and the Cuzco Region. He once said to our class at UC Davis that he could answer any query about colonial Cuzco, but he couldn't tell us how to balance a checkbook or much of anything else. The former was probably true. With regard to the latter comments: the test results are still pending.

Inside the increasingly comfortable minivan, I remembered back to a story Chuck recounted during one of our Latin American history courses. It was about the Siege of Cuzco.

Manco Inca's sabbatical from Spanish supervision, purportedly to gather gold riches for his "allies," had offered the loyalist Sapa Inca & Co. space to spawn a surprise. Both his years of playing puppet to the Iberian conquerors and tactful patience had finally paid off. After having waited in Calca for days to gather a sufficient amount of troops, the Incan attempt to reclaim the city of Cuzco from the Spaniards was initiated.

The rebellion happened on May 6, 1536:

Between 100,000 to 200,000 men had finally been organized by high Loyalist command. The time was now. Accordingly, the loyalist Incan Army marched from the Valley of Yucay (the Sacred Valley) on an ascent toward the highly-propped basin of their former capital, now into its fourth year of Spanish occupation.

|

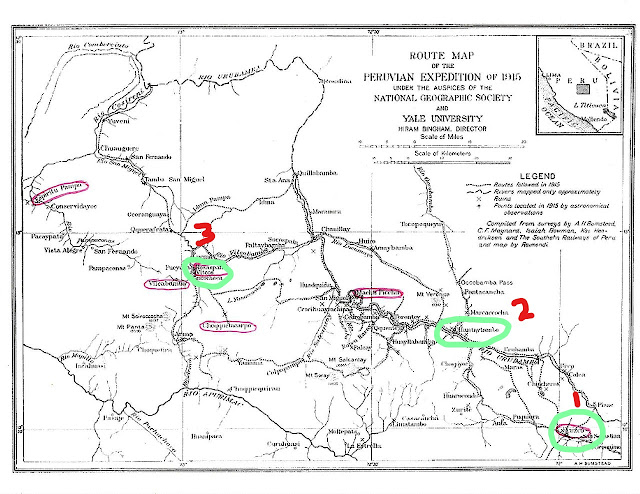

| Refer to the map on the right, Cusco, circa 1530s. |

The hordes of Andeans surrounded the basin city from various angles, though particularly from the heights just outside of Sacsayhuaman, Cuzco's principal and forever intimidating defensive fortress.

At this heightened elevation, the gigantic and still-growing Loyalist army assembled, as it intently awaited the final call. Once having received the cue, the mass of native soldiers ragingly rushed from the hilltop, descending on the mostly helpless Spanish soldiers in the depths of the city, below.

The Spaniards, having only 190 soldiers, though many thousands of Indian allies at their disposal, still had little choice but to retreat from this heavy and ferocious incoming loyalist Incan assault. As a result, the Iberians and their allies took necessary refuge in a pair of enormous buildings located near the main plaza.

The loyalist Incan army, meanwhile, carried on with their barrage of the city, as they importantly claimed control over a majority of its blocks.

My focus returned back to the recesses of the minivan. How's that for an intro to Cuzco! I internally celebrated, impressed that my memory was proving to be fresher than I'd imagined.

I then briefly tuned into how the other passengers in the van were reviewing me. In light of this recounting of the Siege of Cuzco, I mused, who wouldn't react suspiciously to a foreign presence, especially in such a non-touristy location? After all, should I be surprised by their deer-in-headlights' stares and double- and triple-takes? Throughout the course of my many rough Andean ventures, I'd grown accustomed to similar shocked reactions by locals to gringo.

Now, more comfortable, my attention shifted back to the rest of the story of the 1536 Siege.

Over the course of a number of days, back-and-forth skirmishes occurred near the main plaza, where the Iberians were boarded. Needing to relieve their precarious, enclosed position, the Spaniards chose to launch an attack on the walled heights of Sacsayhuaman, the place from which the loyalist Incas had originally entered the city and, since that time, had been the official headquarters of the Loyalists.

Juan Pizarro, another brother of Francisco, thus, led fifty Spanish horsemen, along with hundreds of native allies, to scale up the steep hill, bust through the loyalist Incan lines of defense, and storm the exterior walls of the hilltop fortress to the city.

Though this attack was successful, the resulting fighting was long-lasting and brutal, yielding massive death and injury on both sides. Among the many injured was Juan Pizarro, who later died from his head injury.

Through the day, the fighting continued on full-bore. However, no real momentum shift occurred until the Spaniards sought the use of an arsenal of ladders, a move which helped them scale the giant protective walls of the fortress, where the majority of loyalist Incan soldiers were concentrated.

The Spaniards advanced up the heights of the fortress and furthered their attacks, which eventually forced the loyalist Incas to retreat into a pair of tall towers, towering high over Sacsayhuaman.

Later, subsequent to a long pause in fighting, a majority of the loyalist Incan soldiers were ordered to abandon their position in the tower enclosures. The soldiers who survived the escape, went on to retreat from the heights above Cuzco, eventually moving down to the loyalist safe haven in the Valley of Yucay, near Calca. There, Manco Inca and his high officials were calculating the next move, a new plan was being devised to gather more soldiers so as to bolster yet another barrage on the city. The loyalist Incas would seemingly stop at nothing to recapture their formerly-held capital.

|

| Sacsayhuaman, Cuzco, Peru |

Notwithstanding this proposed rejuvenated push, within days, owing mostly to the slimmed-down loyalist Incan contingent, the Spaniards were able to seize control over Sacsayhuaman. With the main fortress now under Iberian control, the focus of daily fighting then continued intermittently in various parts of the city.

The Spaniards were now on the ascendancy, a trend that would continue over the short-term, especially when the second, large loyalist Incan attack on the city didn't happen. And, as the battle over the weeks and months went on, due to a combination of other factors, the long-term advantage decisively tipped in favor of the conquistadors, the eventual victors of the grueling 10-month affair.

Chuck's words came to me, clear as ever: "And so the Siege of Cuzco was formative in the tale of the two powers. In spite of a handful of attempts to mount other smaller attacks on the capital, the loyalist Incas eventually would have to accept their retreat and seek out lands away from the high Andes so as to maintain a semblance of their empire, their tradition, and their existence.

"It wasn't until Peruvian independence in 1824 that the Spanish would give up control over the city, though they would be threatened periodically by native revolts."

A transpiration in the minivan brought me back into my body. At long last, the long-awaited passenger had arrived. The girthy thirty-something year-old man promptly piled in, sitting heavily, smack-dab in between me and my former neighbor with whom I'd been cordially chatting.

It was the usual stuff: country of origin; reason for traveling; destination of current venture; etc. Intriguingly, the Cuzqueño did mention his work as an archaeologist and his having to return to Quillabamba to the new museum there. This grabbed my attention and interest and, needless to say, had me eager to know more.

However, for the time being, our abrupt physical split had led to an immediate conversational schism, since our new neighbor took the introverted approach, which put a silent damper on the formerly lively conversation and nascent rapport.

Reflection time thus commenced, yielding an opportunity to witness the simply astonishing landscapes along the ascending road to Chinchero, and beyond. Not only was I afforded the time to record the high Andean contours, textures, and colors, but I was able to memorize the myriad climbs, falls, twists and turns throughout this mesmerizing, mountainous region.

Just as we were making our way out of the basin of Cuzco, I remembered something that Hiram Bingham had observed when he was exiting the city back in 1911.

"At the last point from which one can see the city of Cuzco, all true Indians, whether on their way out of the valley or into it, pause, turn toward the east, facing the city, remove their hats and mutter a prayer...the custom undoubtedly goes far back of the advent of the first Spanish missionaries. It is probably a relic of the ancient habit of worshiping the rising sun. During the centuries immediately preceding the conquest, the city of Cuzco was the residence of the Inca himself, that divine individual who was at once the head of Church and State. Nothing would have been more natural than for persons coming in sight of his residence to perform an act of veneration. This in turn might have led those leaving the city to fall into the same habit at the same point in the road."

It seemed to me that Bingham was perhaps exaggerating when he said that "all true Indians" practiced this custom. Nevertheless, he went on:

"I have watched hundreds of travelers pass this point. None of those whose European costume proclaimed a white or mixed ancestry stopped to pray or make obeisance. On the other hand, all those, without exception, who were clothed in a native costume, which betokened that they considered themselves to be Indians rather than whites, paused for a moment, gazing at the ancient city, removed their hats, and said a short prayer."

Back in the minivan, my attention was immediately captured by a passenger sitting a row in front of me. He was voicing something in what surely had to have been Quechua.

"A Ausangate, Salqantay, Wanakauri...!"

Regardless of my incomprehension, his words felt authentic, intentful, and reverent.

"A Ausangate, Salqantay, Wanakauri, Pachatusan,

Saqsaywaman aukikuna!"

As we rode, I continued to watch the man. He was peering toward the mountain peaks, whilst whispering the words and constantly crossing himself in a Catholic way. It would only be years later, following an improvement in my Spanish and familiarity with Quechua, before I would recognize this utterance as a traditional prayer, honoring sacred sites and the sacred mountain peaks, or Apus.

("Oh guardian spirits of Ausangate, Salqantay,

Wanakauri, Pachatusan, Saqsaywaman!")

Diablos! I thought. It appeared that Bingham did know what he was talking about. And, from what I could tell, it looked like the man was just following a timeless local tradition.

The native man had stood out to me right away. Even though I'd been caught up in conversation when he boarded, I'd distinctly noticed him, given his adornment of native attire: alpaca-woven hat and bag, knickerbocker Andean pants, and leather sandals.

There was also something else about him. It seemed he was in a deep state of peace, and this, perhaps naturally, gave me the urge to want to find out more. But, for the time being, our awkward seat positions formed a logistical barrier to any real chance of comfortable conversation.

Thence, I reflected on how everything was coming together: the prayers, the landscapes, the dreams and insights from both today and night before. In fact, I realized that the second-half of my previous night's dream had been a prelude to the legendary Siege of Cuzco.

That's funny. I thought. I don't recall having ever heard about the Spanish preparations prior to the battle in Cuzco. Not to mention, the content of my first-half dream about the last moments of Inca Tupac Amaru, the tale that specially intrigued me.

As I continued to listen to the Andean man's subtle sacred whispers, I thought to myself: Evidently, that's lucid dreaming at its absolute finest.

|

| View from Chinchero |

As we ascended from the niche that is the former capital of Cuzco (11,152 ft.), I reveled in this awesome touch of synchronicity, surely inspired by a tandem of José's recently-told tales from Lima and Chuck's historical insights and inspirations from my UC Davis years. I always knew down deep that none of the time, effort, and attention by way of education, travel, and reading would be wasted. Perhaps that's what trusting one's road is all about.

With the last views of Cuzco coming into sight, I momentarily spaced out, whilst reflecting on where I'd been.

Prior to going to Davis, the Andes had always intrigued me. As a child, I would revel in shows and programs based on the region. These were National Geographic, PBS, and History Channel specials which discussed the history of the Incas, their architecture, and Andean lifestyles, livelihoods, and societal customs.

One documentary I vividly recall showed the way in which Incan bridges were woven using rope made from ichu grass. The detailed, intricate patterns of weaving and knot-tying utterly enthralls me now, let alone those moments of viewing the art as a seven-year-old. Even though I didn't mention it much to others, images from these dated docs had lasting effect in my imagination, even up through present-day.

|

| Chuquichaca Bridge |

Another documentary that will always stand out detailed the khipu, the ancient knot-tied corded instrument that the Incas used to tally important practical, societal, and political information from all over the empire. This genius creation was devised in lieu of an alphabetized writing system, and it was a principal way that the empire was able to be organized, function, and expand.

|

| Khipu Keeper |

|

| Khipu |

Added to watching video and film, I've read a lot. This started in 2002, and hasn't stopped for nearing 20 years. History, anthropology, sociology, novels, testimonies, travel narratives, you name it, I've either heard of it or read it. Book and articles about ancient Peru, the Incas, the pre-Incas, colonial Peru, modern-day Peru, and anything else about the country and region.

I've often told people: "In college, I studied cultural anthropology, but what I really wanted to study was traveling." So, after my graduation from Davis in 2004, I traveled to Peru. It was a two-and-a-half month stay that was so impactful that I've now been to the country on nine occasions in total. I've volunteer taught on two trips, including my inaugural visit. At one point, I almost started a travel agency. From 2005 to 2010, I visited the country six times. After that, I've taken four-year breaks, visiting Peru in 2013, 2017, and 2021.

Throughout that time, I've met a number of wonderful people, Peruvian or otherwise. I've even met a girlfriend or two. One girl, became my partner for nearly two years. This romantic relationship was invaluable in that it helped connect me even further to the culture, history, society, and, perhaps more than anything, the language. My Spanish skills exponentially improved having participated in this relationship.

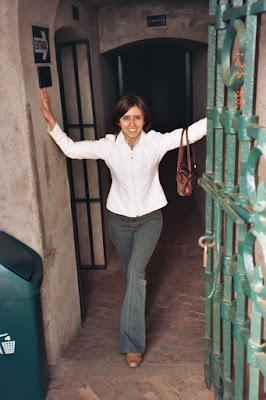

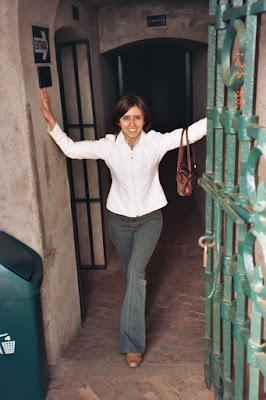

|

| Brenda |

The other girl, Brenda, was a good friend who acted as my Peruvian liaison, selflessly and lovingly orienting me to the country. She, after all, was my connector to Jose, her dad, who promptly took the reins from his daughter, while assuming the role of ambassador to the country and everything that goes with it. José's long-running series of episodes and lectures grounded me in Peru's past and present. For this relationship was so fruitful that it immediately acted as a springboard for my future and forever ventures to the country.

|

| Jose and Brenda, Lima, Peru. |

The minivan's horn sounded loudly, as everyone onboard braced their armrests. While we prayed to avert Cuzqueña catastrophe, the driver swerved to avoid a pair of straggling sheep still in the roadway.

Following the pilot's successful maneuvre, I couldn't help but think: How's that for a swift return from my internal landscapes of learning, love, and language to the external ones immediately up and outside of the Cuzco basin.

Up on the sacred perches of Chinchero (12,343 ft.), one observes the quintessential Andes. In my extensive travels through the majority of this continent-long mountain range, it's safe to say that there's simply no place like here.

All throughout greater Chinchero, green grass, red clay, and brown dirt divinely blend into heavenly hills of fields that expand and extend out infinitely, forever undulating away into distant valleys on the horizon. I, once again, could see why my choice to come back was the right one. After all, I'd been here twice before, with pictures to prove it, and each and every time I come, I sincerely, passionately want to stay. Forever.

|

| The blending of Chinchero hues |

Smoothly flowing along the Chinchero heights, my memory caught hold of a story I'd once read. It was about Hiram Bingham, and how, circa 1908, his first venture through the region had all come about.

The invitation came to his Yale office on the morning of Tuesday, the 22nd of February, 1908.

We sincerely hope you receive this letter in good health.

Our previous correspondence from months back had hinted at plans of organizing a formal gathering of the most educated and prominent of social and hard scientists in one place in the Americas.

He immediately perked up in his seat:

Now, after several months of planning, such an occasion has finally been set in motion.

Thusly, we'd like to cordially invite you as a specialist to the First Pan American Scientific Congress, which will take place in Santiago, Chile in December of this year - 1908.

Your attendance would be nothing less than an honor, given that we see your expertise and insight lending brilliantly to the experience at the inaugural conference.

The First PASC organizers

|

| Hiram Bingham at work |

To describe Bingham's emotions in that moment would be futile, since this opportunity was really just a result of the last 15 years of his academic life, probably longer. As a pioneer of Latin American Studies, Hiram Bingham had an impressive CV: he completed his undergraduate studies at Yale, earned his Masters at UC Berkeley, returned east to Harvard for his Ph.D., and went on to be a lecturer in Latin American History at Princeton; then, a few years later, at Yale.

South America was his expertise and passion. The time was now for this rising academic star.

"Hola, qué tal? (Hi, how are you?)" A voice cut through. It's cordial tone effectively "woke me" from my daze. I found it was the same native man sitting by the window in front of me.

I guess our distance hadn't been too great to get acquainted, after all. He next voiced something that I couldn't quite make out. "Way-naya kakuy-nis, ama-pony machu-yachis..."

It was obviously in Quechua, as my confusion was real.

The neighbor with whom I'd been chatting on the other side of the van looked over with interest. And, in seeing my shock, he decided to intervene. "He said, 'waynalla kakuynchis, amapuni machuyachischu'."

My look continued to speak.

My neighbor continued, explaining, "'waynalla kakuynchis, amapuni machuyachischu'. In Quechua, this means 'always be young, never grow old'. It's a blessing that Andean people say to one another. It's a kind of well-wishing."

I nodded in recognition to the native man's kindness. "Gracias. Gracias por decirlo. (Thank you. Thank you for saying that.")

He nodded back, now, with an even brighter smile, as he asked me in Spanish, "ya has estado en Pisac? (have you been to Pisac yet?)" He referred to a principal city in the Sacred Valley, a destination for the majority of travelers to Cuzco.

"Sí, estuve allí los dos últimos años. (Yes, I was there the last two years.)" I said.

"Wow! Tantas veces ya? (Wow! That many times?)" The man awed. "Y por qué? (And why?)"

I had to think for some time. His question was complicate, after all. And he deserved a complex, complete answer. "Bueno, esa es una muy buena pregunta. Veamos que Perú y la región de Cuzco, en particular, siempre me ha llamado la atención y me ha provocado el deseo y la necesidad de saber siempre más. (Well, that's a very good question. Let's just saw that Peru and the Cuzco Region, in particular, has always called my attention and caused me to want and need to always find out more.)"

The native man gave a thoughtful response. "Lo entiendo. Es un lugar muy hermoso, no? (I understand. It's a very beautiful place, isn't it?)" His contentment on even further display by way of his jovial reaction.

"Sí, es muy hermoso. Quiero seguir regresando más y más. (Yes, it's very beautiful. I want to continue returning more and more.)"

He then mentioned another place. "Fuiste a las Tres Lagunas, en lo alto de Pisac? (Did you go up to the Three Lagoons, high above Pisac?)"

I had to pause a second to comprehend his question, after which I eventually formed a sufficient response. "No... nunca he escuchado de ese lugar. (No, I've never heard of that place.)"

His face lit up, as he explained, "Las Tres Lagunas están entre 4,000 a 4,250 metros (14.000 a 15.000 pies) de altura. Aunque vivo con mi familia en la primera, las tres están muy conectadas. Tenemos todo lo que necesitamos allí arriba. El pescado de las lagunas, las llamas de nuestros rebaños, y la quinoa, las papas, las verduras y las hierbas de nuestras chacras. Deberías visitarlas algún día. (The Three Lagoons are between 14,000 and 15,000 ft. Even though I live with my family at the first one, all three of them are very connected. We have everything that we need up there. Fish from the lagoons, llama from our herds, and quinoa, potatoes, vegetables, and herbs from our farms. You should visit there, someday.)"

"Gracias," I said, awed by his description, "me parece muy interesante. (Thank you, that sounds very interesting.)" I then added, "siempre busco lugares así. Lejos de todo. (I always look for places like that. Away from everything.)"

The native man continued, now with a certainty to his voice. "Es un lugar sumamente bonito, realmente alejado del ruido. Un lugar que puedes visitar para ver una manera muy distincto de vivir. (it's an extremely beautiful place that's really far from the noise. A place you can visit to see a very distinct way of living.)"

He then said something that shocked me, albeit in a good way.

"Si piensas que Chinchero es increíble, las vistas del paisaje, las chacras y los lagos, entonces realmente no querrás dejar las Tres Lagunas. Te animo a que vayas. (If you think that Chinchero is incredible, the views of the landscape, the farms and lakes, then you'll really never want to leave the Three Lagoons. I encourage you to go.)"

I was blown away. His mentioning of my not wanting to leave from here. How would he know those were my exact thoughts? I wondered. Of course, these reactions to Chinchero's landscape are probably normal for most people who visit. But, he said it in such a clear, matter-of-fact way, as if he'd read my mind.

"Mi nombre es Celestino. (My name is Celestino.)" He affirmed.

We shook hands. "Yo soy Patricio. Un gusto conocerte. (I'm Patrick. It's a pleasure to meet you.)"

"De igual manera, amigo. (Likewise, my friend.)" Celestino said.

He then turned forward to tend to his young daughter who sat next to him. She was hardly able to keep awake, as her little-human head bobbed at the mercy of the minivan.

Celestino's vivid description of the Tres Lagunas really caught my attention. His promise of the Lagoons' close connection with Nature, and all that goes with it, sounded very alluring, like something I had to investigate along the road. Surely my intrigue also owed to this man's fascinating mystical mystique. Through the course of it all, from his state of calm, to his prayers, to his words about the Three Lagoons, he seemed to be as genuine as they get.

Notwithstanding any future plans, our present road, however, swiftly continued on, as we ever-so-slowly witnessed ground altitudinally give way, leading us down. Down. Northerly down to the home of Heaven on Earth: El Valle Sagrado, the Sacred Valley.

And it was here, on this subtle downward climb along the Valley's southern wall of eternity, that another tale of UC Davis or, perhaps, Lima origins entered squarely into mind, eventually spiraling open in my imagination.

"Muévense! Los españoles seguramente nos están siguiendo ahora! (Move! The Spaniards are surely trailing us by now!)" yelled the general as the harried pace of loyalist Incan feet sped along even quicker.

The escape from the twin towers at Sacsayhuaman had been a relative success, for the loyalist Incas knew their chances had certainly been dwindling and would've been dangerously slim had they stuck around Capital Hill much longer. Thus, the race through the night was on to reassemble at Calca, the place from which the native Andeans proposed to ramp up an even larger, more vigorous contingent.

Hurriedly descending the mountainside, the weary warriors made their way along the ancient trail; just one of many that connect the capital to its corn. As the line of soldiers marched, the majority of them surely intuited the nearing junction whose road extended out toward the distant, sacred, spherical gardens of Moray. Using this crossroads as a distance meter, the loyalist soldiers knew that the core of the Valley at Yucay was within a quarter-night's jaunt. After that, the main headquarters at Calca would be reached a half-day later, while journeying easterly along the Urubamba River.

"Apúranse! Tendremos poco tiempo para descansar. Los refuerzos estarán listos para partir a nuestra llegada. (Hurry up! We'll have little time to rest. The reinforcements will be ready to depart upon our arrival.)" The same, singularly-focused general affirmed, unaware in that moment of any proposed Plan B.

If clocks had been available in 1537, one would've read: 1:35 a.m. If thermometers had been around, one's mercury would've fallen to 7 degrees F (-13.9 degrees C).

The time, circa the 21st century, was 5:30 p.m. And we, fortunately, still had daylight to work with. From here, the Andean landscape, more than ever, wonderfully opened up to us all, as our minivan plowed along at its forever schedule-dependent, brisk pace.

The praying commenced anew. "A ancha hatun illariy ruraqe! A Pachamama!" He repeated it several times, producing a similar effect to that of the first prayer.

After a drawn-out pause, Celestino turned back to me. "Esto significa, 'Oh, Creador supremamente resplandeciente! Oh, Madre Tierra'! (This means 'Oh, supremely resplendent Creator! Oh, Mother Earth'!)"

I smiled. His description seemed a perfect match to what unfolded outside our window. I could only imagine what it was like for the loyalist Incas during their retreat from Cuzco, circa 1536. They, too, had journeyed along this same magisterial high Andean plateau, with its mixture of greens, reds, and browns, which was now accentuated by our entry into the golden hour, as the shadow-and-light play was simply on stunning, glorious display.

Minutes later, I heard some fussing going on next to Celestino. Apparently, his toddler had just woken from her afternoon nap. After some back and forth, the father finally sought resolution by asking his daughter to salute me.

"Cómo te llamas? (What's your name?)" I broke the ice.

Her eternal black eyes looked up, stunning me right away. For in just one glance, I'd been gifted the universe.

Her red cheeks popped off of her face, as she turned away from me in embarrassment. "Ah, por favor, Chaska. No seas asi! (Oh, please, Chaska. Don't be like that!)" Her father laughed, as she continued on with her endearing antics.

Celestino, having already let her name out of the bag, then explained. "Su nombre es Chaska Flor. 'Chaska', en Quechua, significa 'estrella'. 'Flor' significa 'flor', en castellano. Ella es 'mi flor de las estrellas'. (Her name is Chaska Flor. 'Chaska', in Quechua, means 'star'. 'Flor' means 'flower', in Spanish. She is 'my flower of the stars'.)"

I hadn't known that such utter beauty could be summed up so magnificently in just two words.

I then contemplated Celestino's name. It seemed that the heavens played a role in his name as well. 'Celestino' in English means 'celestine'. This immediately guided me in my memory to the popular spiritual book, The Celestine Prophecy.

I was blown away by the synchronistic nature of these connections. Perhaps I was living out the "Celestine Prophecy" itself?! I mused. For everything, in that moment, and, so far along this journey, felt so fluid and right, reminiscent of a state of consciousness and theme discussed in this 1990s' best-selling book.

As I would find, this beauty on display in synchrony, in human-beings, and in their names would, once again, translate back over to landscapes just outside of our window. It was considerably prior to the profoundest point, along the slowly descending Andean heights just past the turnoff to Maras and Moray, that we caught the first glimpses of what is, for me, the prettiest valley in all of Perú.

I thought back to José's talk about this incredible place. I could, once more, feel the humid air of Lima coming over me anew, as I felt encouraged to recall the plenitud of information shelled out by the Professor in one of his many impassioned lectures from the coastal capital.

I'll never forget what he said. And, particularly, the way he said it. "Cuando vayas allí, Patricio, sólo tendrás que ver la grandeza de esas montañas, 'Las Paredes de la Eternidad', me gusta llamarlas, y sentir el aire andino.... y entonces lo sabrás. (When you go there, Patricio, you'll only have to see the greatness of those mountains, 'The Walls of Eternity' I like to call them, and feel the Andean air....and then you'll know.)"

"'Las Paredes de la Eternidad'" I whispered to myself, caught up in the overwhelm of these staggering mountains, like I'd never seen. That is, until two years before. Then, again the year after. Now, for the third time through the minivan's present perspective. Oh, how this place just never gets old!

|

| a view from the ruins at Pisac |

The Sacred Valley is the source of integral historical towns such as Pisac, Calca, Yucay, Urubamba, Ollantaytambo, and, eventually, western-most Machu Picchu. These places, to paraphrase Professor José, were, at their root, just some of the hubs whose produce, primarily maize, was responsible for feeding and providing chicha (that sacred, fermented corn drink of the Andes) to the bodies of souls in the heart of the Incan empire.

|

| corn farmer at work |

The legendary Urubamba, or Vilcanota, River, now and forever viewable from this high-altitudinal perch, was and is the great water-source, flowing east to west, connecting Pisac to Machu Picchu. A scant, westerly hour from easternmost Pisac (photo above), sits the town of Yucay, hitherto the heart of this mighty valley. In fact, what's today known as the Sacred Valley was up until recently referred to as the Valley of Yucay.

Yucay was principally significant for being the location of the enormous estate of Manco Inca (seen above), an heirloom of his father, Huayna Capac (ruled from 1493-1524). Ruling the Incan empire from 1533-1544, Manco Inca was an example of a savvy, tactful, and prideful leader.

|

| Manco Capac |

Upon the arrival of the Spanish, Manco Inca worked with the Iberians, becoming an ally (read: puppet) in the first months of Spanish-controlled Cuzco. After sensing leverage points during the latter part of three years, Manco, little by little, stretched his boundaries and, eventually, as discussed above, went on to rebel against the Spanish, as evidenced in his leading of the Siege of Cuzco.

There was another event that occurred subsequent to the Siege that would be part of shaping the next few decades for the Loyalists.

The mood inside of Manco Inca's abode was as tense as ever. Amongst the din of voices, one cut through the rest. "We need to decide which option is better."

The room of high officials, military and otherwise, fell utterly silent after the Sapa Inca's interjection. So silent, in fact, that even a pin would not dare drop.

"Realistically, what is our best move forward? Intip Churin, the Son of the Sun, asked, looking around to his fellow decision-makers. "Could this be it? Could it be the time to let go of Cuzco?"

This was a question that only a few were willing to consider, since, after the Loyalists were suffering from an acute case of tunnel-vision due to months of preparation, strategizing, and fighting.

A response finally appeared from Manco's closest confidante. "How about we battle them here in the Valley of Yucay? The especially clear thinker proposed. "After all, we could force them to have to come to us."

Whispers filled the space as those both for and against the question of "should-I-stay-or-should-I-go" laid into one another. This was a topic few were willing to contemplate hitherto. However, now, and from here, there would be only one way through. It was clear: a choice had to be made.

José reappeared in proceedings. "Aunque los incas leales sufrieron una derrota en la capital, su resultado ayudó a aumentar la moral y el impulso de los incas. Y, a la hora de la verdad, Manco Inca sólo quería que ese impulso creciera. Por lo tanto, desde el corazón del Valle de Yucay, los leales se dirigirían al oeste a lo largo del Urubamba, con la intención de manifestar una nueva batalla con los españoles. Esta vez, a principios de 1537, sería en sus términos y en su terreno. (Although the loyalist Incas suffered a loss in the capital, its result helped build Incan morale and momentum. And, when it came down to it, Manco Inca just wanted that momentum to grow. Therefore, from the heart of the Valley of Yucay, the Loyalists would head west along the Urubamba, intent on manifesting a new battle with the Spaniards. This time, circa the start of 1537, it'd be on both their terms and on their terrain.)"

|

| Yucay, Cuzco, Peru |

"Patricio, escucha! (Patrick, listen up!)" José's voice was now emphatic. "Respecto a la Encomienda de Yucay, se convirtió, durante el Estado Neo-Incaico (1537-1572), y debido a su gran tamaño y alto valor, en una fuente de disputa de larga duración entre los incas leales y los españoles, cuyo botín acabaría reclamando esta última potencia... (As far as the Yucay Estate goes, it became, during the Neo-Incan State (1537-1572), and due to its expansive size and high value, a source of long-running contention between loyalist Incas and Spaniards, the spoils of which the latter power would eventually claim...)"

José then took particular pride in the last part. "...aunque la sangre incaica seguiría y, por tanto, estaría siempre presente. Siempre! (...although Incan blood would still and, thus, forever be present. Always!)"

"Fascinante, José. (Fascinating, José.)" I remarked. "Cuando yo vaya allí, quizás haga un saludo a los incas de tu parte? (When I go there, maybe I'll give a salute to the Incas for you?)"

Catching my tongue-in-cheek intent, the Limeño laughed like only he does. "Muy amable, Patricio. Muy amable. (Very nice, Patrick. Very nice.)"

Journey to the Sacred Valley: A Blast from the Profane Past

"Muy gracioso, Patricio. Te agradecería mucho que me honraras cuando pongas tu alma en el Valle Sagrado. Sin embargo... (Very funny, Patrick. I would very much appreciate your honoring me when you set your soul in the Sacred Valley. However...)" the Limeño confessed, whilst smiling, "...la historia aún no ha terminado. (...the story still hasn't finished.)"

|

| View above Maras, looking down toward the Sacred Valley |

My focus returned.

"It was somewhere around the Yucay Encomienda, circa 1537," the Professor cleared his throat and continued, "that the same rhythm of harried, constant footsteps still scooted along, now, upon the moist clay of the Urubamba riverside. This uniformity of sound endured against the river's current for the entirety of the early morning."

If one looked carefully, a long-stretching line of soldiers, like an infinite trail of marching Andean ants, could be seen from here, at river's base, all the way back up the gargantuanly-walled mountain side. The ones at the tail were the last of the retreating loyalist Incan soldiers making their way down from Cuzco to the eventual rallying point in easterly Calca.

Only moments prior to now, it had been decided that the majority of troops would next move to westerly Ollantaytambo, on the other side of the long valley. Therefore, the military masses would trace along the western flows of the Urubamba River. And, sometime around dusk, they'd arrive to the well-fortified, formidable citadel, the setting and scene of an impending battle.

It was a viewpoint almost unanimous in Incan circles: given the numbers of embedded Iberians and native allies in Cuzco, opting to advance anew on the Spanish-held city wasn't a safe option. Ollantaytambo, by contrast, was perceived to be a perfect place for potential loyalist Incan glory. Of this, the Sapa Inca & Co. were optimistic, if not certain.

"Sabes que los españoles vendrán. (You know that the Spaniards will come.)" Manco Inca's main general intuited. "Esta es nuestra oportunidad de reducir su número... (Here's our chance to dwindle their numbers...)"

Manco Inca nodded, now convinced that the tense discussion days' prior had paid off. Despite the outliers to the plan, the strong majority of loyalist leadership were in-step with the Inca.

That evening, as the Loyalists prepared their many thousands for an entrenched battle with the Iberians the following day, a growing, palpable tension dominated the camp. Once again, this time at and around Ollantaytambo, they knew that destinies would be determined.

José kept on with his Lima lecture. My mind, however, drifted back to present day and then away to another time. My imagination was enlivened by an experience I'd had a couple of years' prior to my minivan journey into this area of the Sacred Valley, when I'd spent ample time here and knew Yucay for something very, very different.

During that trip, I had with me a worthy copilot, a Peruvian man aptly named Jesús. The flamboyant Limeño-living-in-Cuzco, principal of the language school I volunteered at, and self-admitted descendant of Divinity, was my travel partner for a four-day trot through various sacred Andean towns.

Our untrusty 1987 Nissan Sentra, rented from a contact in Cuzco, offered us a precarious freedom to venture to whichever places we desired. Precarious, due to its questionable mechanical shape and shaky structure. Freedom, since the car was an imperfect provider of an alternative to a schedule-ruled taxi or bus, the more popular options of Peruvian transport.

From the prop at Chinchero (12,343 ft.), we descended to Maras (11,060 ft.), an ancient town known for its salt mines four kilometers from the town center. Bypassing on the chance to check out the 5,000+ polygons of mountain salt, Jesus and I roamed through the village, onto and over somebody's extensive farmland, and exhaustingly up a hillside that seemed to stretch forever in the four directions of the former empire. Thereabouts we found a place to rest, as we promptly set up camp.

|

| Maras, Cuzco, Peru |

This late afternoon truly had the makings of a memorable experience, given our choice to pitch our mobile home on this magnificently-perched plot, one that simply provided a most spectacular of high-Andean vantage points.

|

| Maras, Cuzco, Peru (with the Sacred Valley in the distance) |

"Qué vista, Jesús! (What a view, Jesus!)" I celebrated.

His response was fitting. "De nada, Patricio. (You're welcome, Patrick) A few seconds on, he asked, facetiously, "qué harías sin mí? (what would you do without me?)"

"Yo haría todo sin ti, amigo. (I'd do everything without you, buddy.) I responded, straight-faced and sarcastic. "Pero... (But...)" I returned back to my original intention, "...con todo esto, parece que la caminata hasta aquí no fue para nada. (...with all of this, it looks like the hiking up here wasn't all for not.)"

Our silence matched the early evening's sheer stillness. Fittingly, Jesus pulled out a bag of goodies he'd purchased at the store prior to our exit from Cuzco. Opening up a white cloth to reveal a mix of materials, he'd brought roman candles, coca leaves, a stick of palo santo, pictures of the saints, and dried flowers, among other objects.

When I asked what the meaning of the fuss was all about, the Limeño responded, emphatically, "Patricio. Sabes que soy de Lima, pero mi sangre es incaica hasta la vena, la arteria y el corazón. ¿No se nota? (Patrick. You know I'm from Lima, but my blood is Incan to the vein, artery, and heart. Can't you tell?)"

I nodded, especially entertained by Jesús's theatrics, which were so typical of the man.

"Bueno. (Well.)" He continued. "Aquí en los Andes, esto es lo que hacemos. Es una bendición tradicional que se hace cuando y donde sea. Esta ofrenda es una forma no sólo de limpiar la energía de la zona, sino también de pedir que vengan cosas buenas, así como de dejar ir las cosas del pasado. (Here in the Andes, this is what we do. It's a traditional blessing - "ofrenda"- that happens whenever and wherever. This offering is a way to not only cleanse the energy of the area but also to ask for good things to come as well as to let go of those things of the past.)"

"Ah, como una oración? (Ah, like a prayer?)" I reasoned.

"Claro, Patricio. Claro! (Exactly, Patrick. Exactly!)" He exclaimed. "Así que con esas cosas que quieres dejar ir en mente y con las cosas del futuro que te gustaría crear, sigamos adelante. (So with those things you want to let go of in mind and with the things of the future that you'd like to create, let's go forward.)"

As we enjoyed the niceities of the ofrenda in the heart of Andean golden-hour, the cordillera breeze started to pick up. This element added a synchronistic sensation to the stunning spectacle, as my imagination, meanwhile, began to drift to a time nearly five centuries in the past, when yet another conflict between Old- and New-World was precariously brewing.

The first of the Spanish allies were making their push toward the crossroads at Urubamba. From there, the scouts had informed leadership that the few hours leading up to the citadel of Ollantaytambo would officially be the start to the chaos.

"Tenga cuidado, comandante. (Be careful, commander.)" The scout warned. "Tienen puestos de avanzada para tratar de impedir que lleguemos a la ciudadela. Recomiendo enviar primero a los aliados como primera línea. (They have outposts set up to try and stop us from even making it to the citadel. I recommend sending the allies first as a frontline.)"

"Bueno. Algo más? (Okay. Anything else?)" Pizarro sternly asked.

"Sí, señor. Suárez me informó que las escarpadas de Ollantaytambo son más inclinadas de lo que había pensado. Tendremos que romper infinitas líneas de soldados si queremos salir victoriosos. (Yes, sir. Suarez informed me that the steeps of Ollantaytambo are more inclined than he'd thought. We'll have to break infinite lines of soldiers if we are to be victorious.)"

The commander resettled himself. "Percibo dudas, Arias? (Do I sense doubt, Arias?!)"

"No, señor. (No, sir.)" The scout coiled. "Es...es sólo una preocupación que tengo sobre lo que dijo Suárez. (It's...it's just a concern I have about what Suarez said.)"

"Suficiente, Arias. Vete. (Enough, Arias. Leave.)" The commander scalded.

The warning hadn't been the first to Commander Pizarro. The other scouts had relayed information of what to anticipate on the tasking road ahead: "infinite honda-slung balas, spears, and other melee weapons" would be employed by "an infinity of Loyalists" looking to cause havoc on the Old-Worlders and their friends.

"Por Dios! (God!)" The Trujillo man implored the Divine. "Que sea el momento de librar a la tierra de estos infieles. Le pido a Ud. que nos ayude en nuestro camino y en nuestra lucha. (Let this be the time that we rid the earth of these utter infidels. I ask of You, assist us in our road and in our fight!)"

Hernando Pizarro unquestionably had more riding on the result than anyone else in the Viceroyalty of Peru. But would he find solace?

In spite of not having slept sufficiently on the cold lookout over the Sacred Valley, the next day, our road led us to Urubamba. Here, we stopped for breakfast and a brief look-around the main plaza, which was as peaceful as could be, a setting standing in stark counterpoint to what Spaniards & Friends surely experienced nearly a half-a-millennium before.

From the hub of the Sacred Valley, we headed east, for a five-mile drive to the leisurely town of Yucay (9,380 ft.). While Jesús mixed with a couple of horses posted up on the roadside, I decided that I needed a respite from it all. So, just down the way, I found an empty park just up from the Urubamba, where I took a well-needed siesta.

Whilst wading peacefully in the grass, I opted to take a break from the lessons of history, as I reflected on this inaugural trip to the old Valley of Yucay. It'd only been a day or so since the start, and it'd already been remarkable and memorable for many reasons, most principal among them, my choice in travelmate.

Jesús was a man that defined style. He stood out from the rest not only given his impeccable fashion-sense, but by way of an attitude that was impossible to match. My best description of Jesús would be one part RuPaul, two parts Juan Gabriel (the famous Mexican singer/songwriter), and three parts puma. He was as flamboyant as the first two, and as feisty and primed as the latter; like the wildest of felines, Jesús seemed to always be lurking, waiting, and ready to pounce, when pressed.

Previous to my first trip to Peru, a man with such floridness was the last thing I thought I'd come across in the former Incan capital. After all, I had for years been fed a montage of images of native Andean people, the illustrious ruins of Machu Picchu, the intricate Incan roads, herds of llamas and alpacas, and grandiose architecture of the highest kind. Add to that, the sacred traditional dress, music, and dance, and I thought I had Peru, and, more specifically, the Cuzco Region completely figured out. Or so I thought, prior to my initial touchdown in the 11,000-foot hideout in the mountains.

Given that Jesús was one of the first people whom I met at the Cuzqueña school I volunteered at, every one of these common images of quintessential Andean Peru would be temporarily placed on hold, while having to wait to be discovered. On that unforgettable first day at the language school, I had to accept and assimilate the glory which graced my immediate reality only steps away. I remember it via a combination of recalled visions, emotions, and, fascinatingly, olfactory memories.

Waiting nervously inside of the Andinos Language School just up from Calle Zaguan del Cielo, I graciously received a cup of coca tea offered to me by Juan Carlos, one of the assistants at the school, and the first Cuzqueño I ever met.

Minutes passed, while I inspected the decor of the small comfortable classroom in which I sat. There, I noticed the cleanliness of the establishment, particularly, the white paint of the walls, ceiling, tables and chairs as contrasted with the bright orange of the window curtains and miscellaneous items decorating the tabletops. Surely, I surmised, the work of a fashion-sensible woman.

Next thing I knew, a fabulously floral yet borderline pungent perfume strongly wafted in through the door through which I entered. Perhaps, I mused, one of the female teachers had arrived early to prepare for her morning class.

Just seconds later, the sound of boot to tile floor commenced, greeting my ear as I propped up and out of my early-day daze, post-10-hour bus ride. Perhaps this would be the first Cuzqueña (woman from Cuzco) I would have the honor of meeting, I celebrated.

"Hello." Came the voice, sounding more masculine than my expectations. "You must be Patrick."

I got up to meet the still-shadowed person who spoke. I came to find not a woman, but a 30-something Peruvian man with strong Andean features.

"Welcome to Cuzco," Jesús said, with a bright smile, a clear match to the portrait picture I'd seen on the school's website.

"Thank you," I responded, as I continued to observe what stood in front of me.